By Matey Nikolov / WagingNonviolence.org

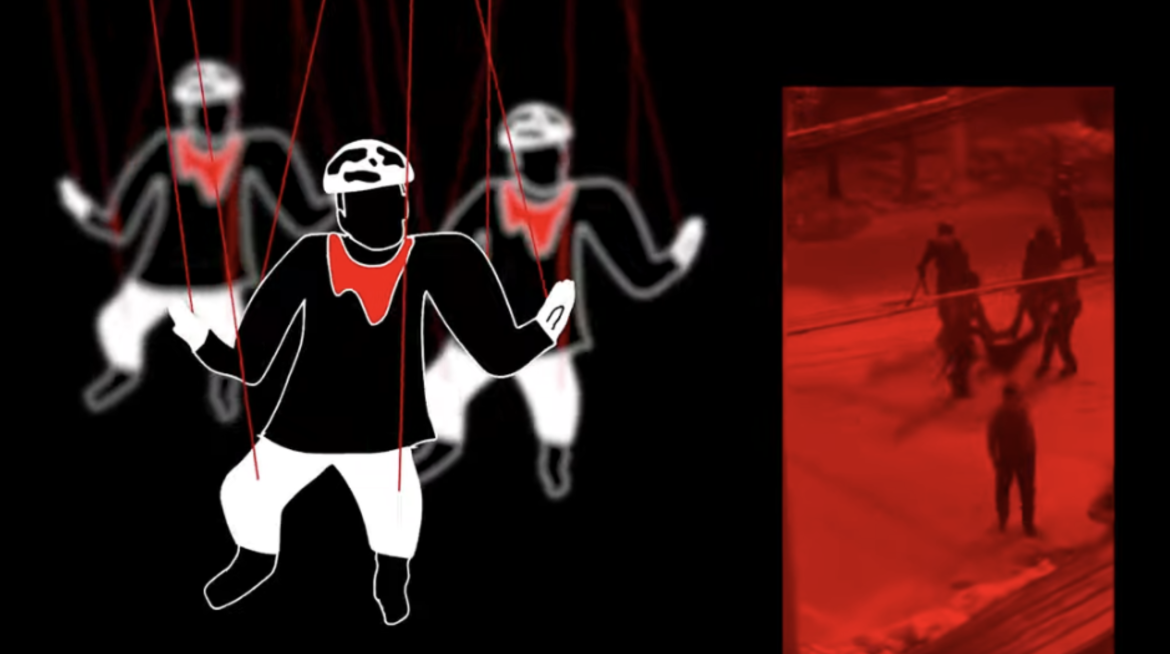

In the music video for the song “Lee 199,” Rap Against Junta artist 882021 raps over a powerful combination of animated sequences and video recordings of police and military violence against the people of Myanmar. Skillfully, the video clip confronts viewers with the brutal beatings and shootings committed by government forces during nonviolent actions on the streets of Myanmar. Rap Against Junta is an alliance of artists and producers who, amid the aftermath of the illegal power grab in February 2021, chose music as the vehicle for expressing their political frustrations.

The video clip is a powerful example of cultural resistance, which can be defined as the broad use of arts, literature, imagery and other culturally embedded elements to oppose unjust ideas and express criticism of political, economic and social issues. Cultural resistance is extremely powerful in raising awareness of an issue and inspiring a call to action.

One of the best-known examples of cultural resistance art is Banksy’s stencil, originally sprayed in the West Bank, called “Rage, the Flower Thrower.” In it, a man is depicted, wearing a scarf and a baseball cap, aiming to throw a bouquet of flowers at someone/something in rage. The stencil conveys Banksy’s well-known dedication to pacifism and nonviolent conflict resolution. Cultural resistance takes many shapes and forms, and as different mediums of communication gain traction so does their application in the fight for social justice.

Rap Against Junta chose animation mixed with real footage to convey the rage, disgust and fear, amongst other difficult emotions, arising from the committed atrocities of the military junta. The power of animation is leveraged and used to express in symbols what words often fail to capture. Furthermore, due to its use of symbolic visuals, animation inspires a different sort of understanding and solidarity, one rooted in empathy rather than reason. Therefore, animation is well positioned to become a powerful medium for cultural resistance.

On solidarity and symbolism

The discourse on public issues like gender equality, climate change and mental health are often accompanied by emotions and feelings that are difficult to capture. One recent example from Poland demonstrates animation’s power to educate and build awareness on topics where words are an imperfect mode of communication.

As a response to the Polish Constitutional Court’s decision to restrict abortion rights in late 2020, some 50 animation students at the Film School of Lodz came together in an act of fear, rage and solidarity to produce a collage of animated short clips. It reached a large audience after being published on the Facebook account of G’rls Room, a Polish alternative feminist magazine.

The video vividly depicts the emotions and feelings experienced by Polish women and men in the aftermath of the anti-abortion bill. The animated content varies widely from depicting drowning women and exploding bellies to evil priests and self-mutilation, and the personal statements accompanying the animations range from “I’m hugging you all,” to “I’m scared” to “My body belongs to me. Not priests or politics!”

The medium allows the viewer to get a better sense of how it feels to be on the other side, which may lay the groundwork for democratic dialogue in the future. Cultural resistance pieces like this one have the power to raise awareness beyond their immediate locality and national boundaries. The bundle of animated shorts was so well-received that it inspired another two groups to assemble their own set of animated clips on the topic of abortion. One by animators from Poznań, a city in west-central Poland, and another by a group of creators from Hungary, who decided to create their own version in support of Polish women.

The mix of animation and real-life footage can also prove to be valuable. In recent Roger Rabbit-style short videos from Myanmar, an animated Burmese activist appears alongside a live-action Ivan Marovic, a veteran from the Otpor movement in Serbia, discussing the urges to use violence against oppressive regimes, distributed tactics of resistance and frustrations experienced by the animated character. Posted on an anonymous YouTube channel called “Pots and Pans,” Marovic shares personal stories and explains the “spectrum of allies,” a strategic framework often used by organizers as they plan actions to identify social groups and strategize how to shift power in the movement’s direction.

Disinformation

For all the good it does, the world of animation has a dark side too. Authoritarian regimes and right-wing troll factories are quick to learn and, in some cases, a few steps ahead. Organized troll farms and governments have resources that are hard for social movements to outperform.

For example, this anonymous pro-Russian video posted on YouTube, loosely translated as “The Russian Invader,” is designed to convince viewers that Russia is the greatest country in the world. It complements the Russian government on questionable grounds and questions the integrity of western democracies. The video implies that Russia’s presence in the Baltics brought prosperity to the people and enabled the production of high-end electronics. On the other hand, the video suggests that the arrival of democracy has impoverished the country, forcing part of the population to clean toilets in Europe. The animation utilizes state-of-the-art visual effects to make the propaganda more “believable,” effectively weaponizing animation and video content.

When adversaries of democracy use their freedom of expression in this way, the risk of backlash or censorship from democratic regimes is minimal. Democracies have and continue to struggle to defend themselves in the face of online disinformation. Censorship and content moderation are extremely divisive topics in contemporary liberal democracies. On the one hand, liberal democracies should defend their citizens and ensure that the digital space can be enjoyed free from intentionally harmful content. On the other, governments should not hold the power to decide what information is or is not available online.

Self-censorship and surveillance

In social justice campaigns large scale success often comes with the attention of malignant actors. To exist and become widely sharable, animation clips require space on the network of servers hosting the internet, also called the cloud. It’s of little importance where on the cloud a video exists, initially as the digital footprint grows with every view, every like or dislike, and every share.

Even if an individual or a group of creators attempt to stay anonymous, once the video leaves their immediate possession it is up to the rest of the people to ensure that such content is shared through end-to-end encrypted communication channels like Session, or anonymous file-sharing platforms like OnionShare. A network of actors is only as safe as the security levels of the network’s weakest link.

Once social justice content goes viral, it becomes exceedingly difficult to minimize the risks for the network. When the animation attracts sufficient attention, it can potentially become a trap. Malware can be embedded inside of the video file once it falls into the hands of bad actors. Thereafter, upon downloading the file locally and engaging with it by clicking on the content, the malware or spying trackers start to collect data. Eventually, when enough data is gathered, through data triangulation and cross-checking with other tracking platforms, it is easy to map out networks of users, and in some cases point out specific identities.

Surveillance and tracking online are nothing new. In July 2021, Pegasus — yet another form of spyware, developed by the Israeli company NSO Group — was brought to light. Once installed, Pegasus allows for the complete surveillance of all mobile phone activity. It could, for example, be installed onto a device via video file sharing. When the receiver clicks and downloads the video before watching, Pegasus gets downloaded as well. It is widely believed that Pegasus was purchased by at least 10 different countries. Therefore, the use of data triangulation and mathematical modeling in mass surveillance make animated videos a perfect vehicle for infecting activist groups and other loosely associated actors with malware.

AI-produced content is just around the corner

Cultural resistance is always changing in attempts to keep up with the evolution of new mediums of communication or to set a new direction in the struggle for global social justice. One of the newest frontiers of cultural resistance is emerging from machine learning.

On Nov. 18, award-winning artist Cecilie Waagner Falkenstrøm displayed her newest piece of art at the Tech4Democracy conference in Denmark. The artwork consisted of a projection of artificially synthesized images of different technological utopias and dystopias morphing into one another accompanied by anonymous robot-like voice narration. The piece conveyed an important message of the power of technology and humanity’s growing dependence on it by demonstrating multiple pathways forward — both futures where the synergy between technology and people works out as well as the ones where it doesn’t.

Source: Matey Nikolov, WagingNonviolence.org (CC BY 4.0)